The trillion-dollar promise of “tap and go” has a quiet price tag, and it’s embedded in almost everything we buy.

From a $4 latte to a $40,000 kitchen remodel, the fees that flow through the card rails are largely invisible to consumers but unavoidable for merchants—and therefore priced into retail.

Follow the money and a simple story emerges: every swipe sets off a chain of transfers among banks, processors, and card networks that collectively drain billions from merchants’ margins each year. The true cost of convenience is higher than most people think, and the profits are among the richest in modern finance.

Table of Contents

How the four-party system extracts value, every time you pay

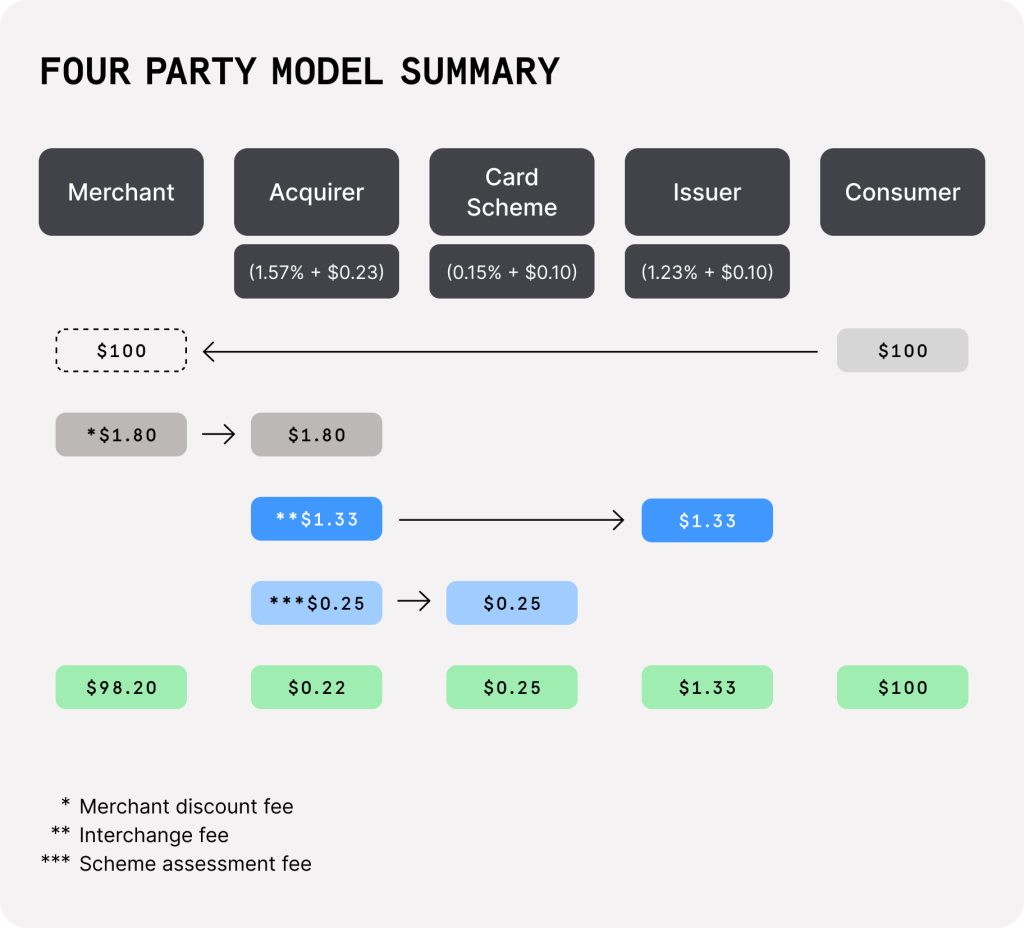

The mechanics reveal a sophisticated toll system. In the four-party model, the cardholder’s issuing bank authorizes a transaction over a network (Visa or Mastercard), while the merchant’s acquiring bank accepts and settles it. The “merchant discount rate” (MDR) the merchant pays includes interchange (paid by the acquirer to the issuer), network “assessment” or scheme fees (paid to Visa/Mastercard), and processing/acquiring markups.

Interchange dominates the cost structure—averaging roughly 2% on credit in the U.S. The total U.S. merchant processing bill reached $172.05 billion in 2023, up 7.1% year over year. Visa’s assessment schedule alone includes a 0.14% assessment on credit volume plus per-transaction and international add-ons—an overlay before any acquirer markup is applied.

Visa and Mastercard don’t issue cards or lend money—they sell access to rules and roads. But in most markets, they are the only roads that reach everyone. Visa’s roughly two-thirds operating margin tells you what a global, two-sided tollbooth looks like when regulation is absent.

The networks’ evolution—from cooperative rails to high-margin toll roads

Their transformation shows in the numbers. Visa reported fiscal 2024 net revenue of $35.9 billion and operating income of $23.6 billion—an operating margin of roughly 66%, off a base of 233.8 billion processed transactions and almost $13 trillion in payments volume. Few businesses on earth scale this large with that kind of profitability on what is essentially a transport layer for value.

Visa began in 1958 as BankAmericard and grew into a global network by the 1970s before consolidating into Visa Inc. in 2007, crystallizing the economics of the tollbooth it operates. Mastercard’s roots trace to 1966 as the Interbank Card Association, maturing from a member-governed utility into a profit engine that sells access to its rails and rulebook.

Mastercard posted 2024 revenue of $28.2 billion and $9.8 trillion in gross dollar volume, with 159.4 billion switched transactions—again signaling a network business that grows with global commerce yet collects tolls at each hop.

American Express runs a different model: a “closed loop” where the company is the network, issuer, and often the acquirer. In 2024, Amex set records with $66 billion in revenue and more than $10 billion in net income.

But where are these profits coming from? Unlike commercial banks, card processing doesn’t come with a “license to print money“. And yet it’s extracting billions of dollars of value from the economy each year.

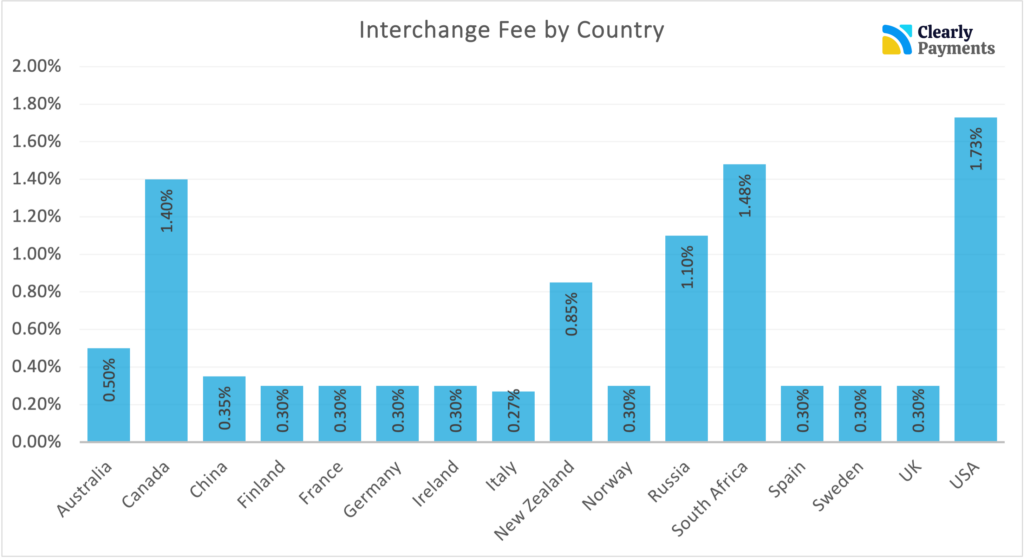

The global fee map: 0.05%-8%

Card processing fees vary between regions. North America has some of the highest average credit card processing fees (around 1.5% to 3.5% or more), especially with rewards and premium cards. Latin America also experiences high fees (about 2% to 4%) with additional costs from currency conversions and local taxes. Other regions generally have lower fees due to regulation and localized payment systems

United States: Credit cards average above 2% in total merchant fees. Debit is regulated under the Durbin Amendment, capped at $0.21 plus 0.05% for large issuers, a lot lower than credit.

Canada: Ottawa struck agreements with networks to cut in-store domestic credit interchange for qualifying small businesses to a weighted average 0.95%. Government estimates forecast about C$1 billion in savings over five years for eligible small firms.

Europe: The Interchange Fee Regulation caps consumer debit at 0.2% and credit at 0.3%—demonstrating that hard caps can work market-wide. However, post-Brexit, networks raised UK-EEA cross-border fees fivefold—debit to 1.15% and credit to 1.5% for online transactions, costing UK businesses £150-200 million annually. Ultimately central planning is just patching the issue, the root problem has to be addressed on a deeper level.

Latin America:

- The average payment processing fee in LATAM is around 2% to 4% of the transaction amount.

- Interchange fees can range from 0.5% to 2.5% depending on card type and transaction nature.

- Assessment fees by card networks are about 0.13% to 0.15%.

- Processor fees vary from 0.2% to 1%, covering authorization, fraud prevention, and settlement.

- Smaller merchants typically pay higher fees (2.5% to 3.5%), while larger enterprises may negotiate lower rates (1.5% to 2%).

- Credit card transactions have higher fees than debit cards or alternative payment methods.

- Brazil capped debit at 0.5% while launching PIX, the instant-payment system that pressures card pricing

- Mexico publishes interchange schedules with debit capped at 1.15% or 13.50 pesos

- Chile implemented caps at 0.8% for credit and 0.35% for debit

What consumers don’t see—and why they still pay

Every fee a merchant absorbs finds its way into retail prices. Academic research shows that card fees create regressive wealth transfers: higher-income consumers using premium rewards cards capture benefits funded by fees built into prices paid by all shoppers, including cash users.

The “true cost of convenience” is visible in macro numbers. U.S. merchants’ card processing costs eclipsed $172 billion in 2023 and continue rising. That burden doesn’t disappear in competitive retail—it gets priced in quietly because few sellers can steer or surcharge without friction.

Not just cards, payments in general are costing us

A recent report from Lightning News revealed that freelancers worldwide are squeezed out by payment providers. Platforms like PayPal, Pateron or Stripe charge up to 12% in fees. In some countries even higher. The estimated annuall toll exceeds $3,69 trillion.

Why cash and bitcoin is king—for merchants’ margins

Cost studies across jurisdictions consistently find that cash remains cheaper for merchants than card acceptance for many transactions. Recent literature reviews confirm cash’s surprisingly low merchant-side cost for conventional point-of-sale transactions.

Card transactions carry chargeback exposure, compliance costs, and potential network penalties that push total acceptance cost above headline interchange rates. Cash has handling and security risks, but no chargebacks, network penalties, or cross-border uplifts.

An even more innovative solution to the “fiat toll booth operator” issue is a decentralized payment network run by independent nodes. A prominent example is Steak ‘n Shake who recently made waves by integrating bitcoin lightning payments at their restaurants.

The chain confirmed that they were able to lower the payment processing cost by 50% while increasing sales by over 10%.

What a $100 sale looks like to a small merchant

In the U.S., a typical $100 credit transaction costs a smaller merchant between $2.30 and $3.00 all-in. Debit with regulated interchange can be under $0.30-$0.40 for the same sale. Cash isn’t “free,” but for that $100 ticket it often remains cheaper than credit—explaining persistent merchant incentives to steer toward debit or accept cash discounts.

The road ahead and how to reduce credit card fees

Cards and digital payments are loved by shoppers. But do merchants actually like them? According to a study, the net benefits of debit cards exceed those of cash and, where checks are evaluated, those as well. The clear conclusion of this work is that, by the time Layne-Farrar undertook her analysis in 2011, acceptance of debit cards generated per-transaction net benefits for merchants that exceeded those of cash.

Two forces will shape the next phase.

First, decentralized payment networks like bitcoin and lighting which allow low-cost, instant cross-border and online payments.

Second, credible alternatives at scale—Brazil’s PIX shows what happens when a central bank sponsors an open, near-zero-cost instant rail.

Litigation continues but provides more noise than price relief. A proposed $30 billion settlement was rejected in 2024, sending parties back to negotiations while existing class settlements continue moving through distribution.

If consumers fully grasped that card fees are embedded into the prices they pay—even when they hand over cash—the politics of payments would change overnight. The tolls are collected in tiny slices a billion times a day, and the takers are doing exactly what they were built to do: turn ubiquity into margins. Until there’s a new road or a new rule, merchants will keep paying—and passing it on.